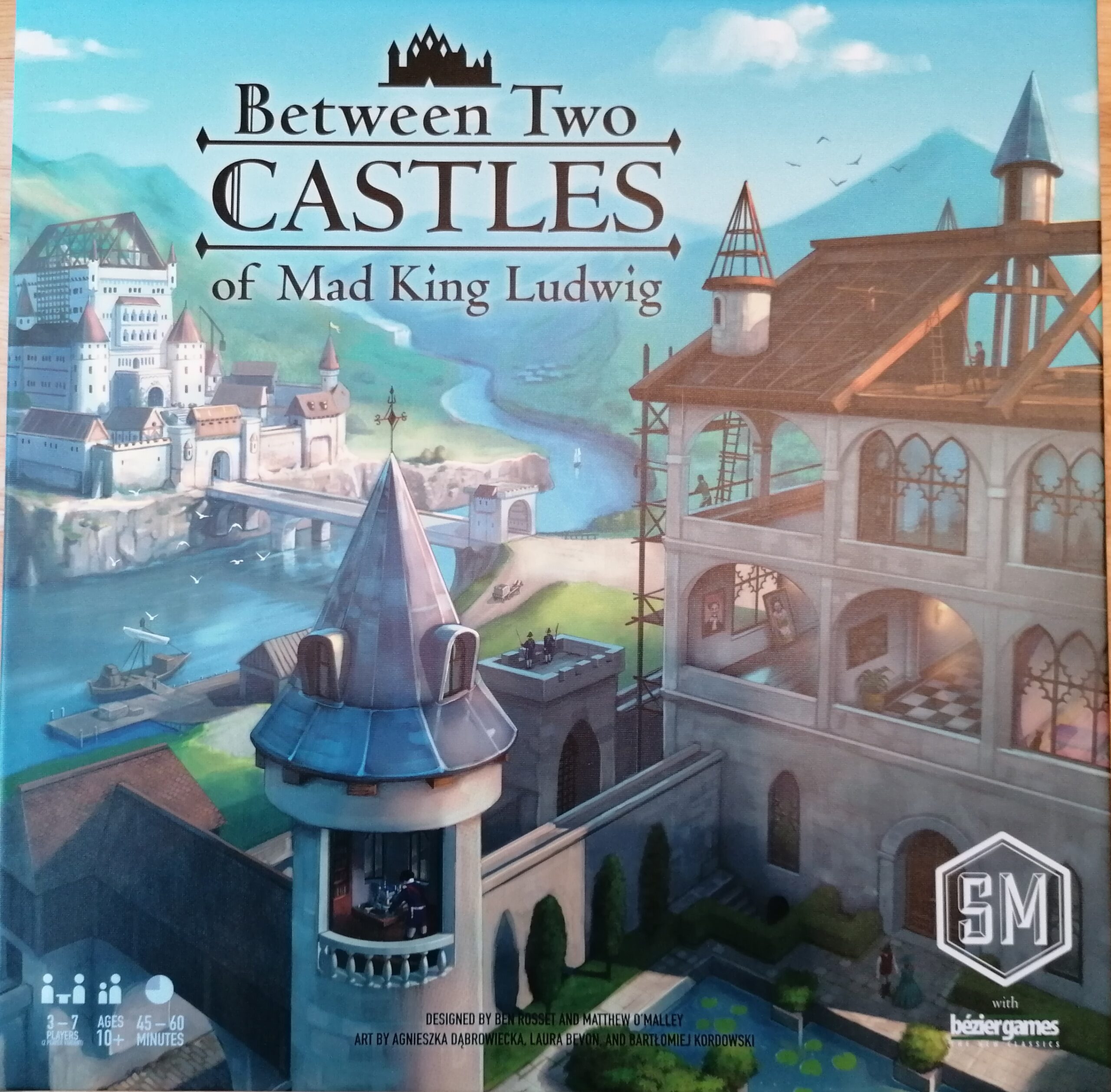

Between Two Castles of Mad King Ludwig is a game which combines two slightly older games. The first one, Between Two Cities, published by Stonemaier Games, was a game where you worked together with your neighbours to build a city, then each player would score their cities, and the lower scorer of the cities they have would be their final score, with the person with the highest score being the winner. The second game was Castles of Mad King Ludwig, published by Bezier Games, where players would buy tiles from a market determined by one of the players in order to build the best castle. Between Two Castles of Mad King Ludwig was put out by Stonemaier Games, in collaboration with Bezier Games, using the gameplay from Between Two Cities, and the theme from Castles of Mad King Ludwig. I have not played either of the original games, so I can’t really draw comparisons to them.

Between Two Castles consists of only two rounds, at the start of which each player will take a stack of nine tiles, choose two (one to go in the castle of their left, and one to go in the castles their right) to keep for this turn, and pass the remaining tiles to their neighbour (clockwise for the first round, anti-clockwise for the second round). Once each player has chosen, they will reveal the tiles, discuss with their neighbours one at a time as to where the tile they have chosen will go into the castle, then pick up the tiles that were passed to them and repeat, until only one tile per stack is left, which are discarded. The game, at face value, is an incredibly simple one, but as with a lot of games put out by Stonemaier Games, there is a fair amount of depth once you look a little closer.

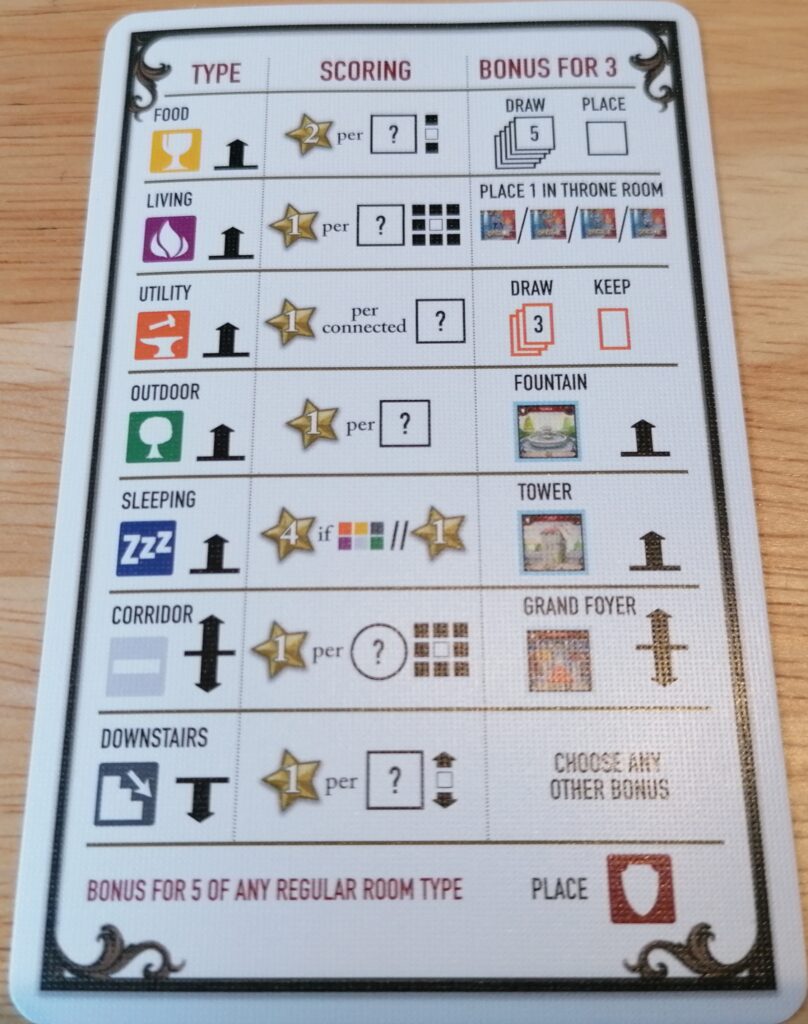

Each pair of players will begin with an asymmetric throne room in between them, with its own scoring agenda based on room type and positioning of the tiles, giving you something to aim for from the beginning. There are seven different room types, all of which have different scoring conditions, most of which again dependent on where the tiles are placed. You can gain various bonuses for placing a third tile of the same type of room, again all different based on the type of room they are, and an extra special bonus if you place of fifth of the same type of room. Essentially everything in-game is communicated by symbology, again usually indicating the type of room and where it need to be placed to score. Despite all this however, the information you need is all very clear, and you get a reference card which not only lists all of the room types and the commonalities in their scoring, it also lists all the bonuses which relate to the room type. I feel like, without this aid, it would be a game where you would need to refer back to the rulebook (which is also very well designed in my opinion), and so to have this included is a great help.

The design of the tiles is key in a game like this, especially the room tiles, as these are the main components of the game. I can understand that some people may consider them to be too small, however I would argue that, as each pair of players is building up a castle containing a minimum of sixteen tiles (excluding the throne room tile), and that this game can handle up to seven players, it would be difficult to play with larger tiles, unless you had a huge table.

In the top left of the tiles is the symbol indicating the type of room it is. In the top right, most tiles will contain another symbol, which relate to the type of ‘wall hanging’ on the tile, which may or may not come into play based on the type of things your castle scores. Between these two symbols is the name of the room, which, while irrelevant to the gameplay, does help inject some theme into the game. At the foot of the tile is how that tile scores, and this is what you will mainly be focusing on. To give some examples, the ‘Swimming Hole’ tile in the top left of the picture looks at the rest of the rooms in your castle, and will score one point at the end of the game for each living room there is, whereas the ‘Hidden Entrance’ tile next to it will score a point for every corridor above or below it in the same column as it is. The way the scoring is done is an enjoyable puzzle for me, and the random draw of the tiles, along with the drafting of tiles, only add to that. Some people, including me in some games, argue that randomness spoils the fun, if only a little. However, I think it is necessary here, as without it, this would be a game that could just be ‘solved’, and in my view, that doesn’t make for a good experience.

Communication in Between Two Castles is unavoidable, as you will have to work with your neighbours well to place the right tile in the optimum position. However, the trick is being able to notice if you are paying too much attention to one castle of the other. As I mentioned, at the end of the game your score will be your lowest scoring castle, so you cannot prioritise one over the other, unless you see that one is falling behind on scoring. Being able to recognise this in game isn’t too complicated, but it’s not especially easy either, as the game moves quite quickly. Luckily, the same will apply to your neighbours on both sides, so even if you don’t recognise it, they might, if only in relation to the castle they are building with their other neighbour.

This is also fortunate because you are more likely to recognise the best place to put a tile, or even the best tile to place. Perhaps you picked a tile with the intent of placing it in a specific spot in the castle on your right, but once your neighbour sees it, they may be able to see an even better one. Or your point of view could change dramatically based on the tile they have picked. You could see that there is a better way to place your tile now, or even more drastically, you could change your mind on the tile you had set aside to place in that castle. This didn’t really happen when I played, as we tended to reserve a tile, in our minds at least, for each castle, and not consider switching, but there is nothing in the rules which states that you have to do this.

Something I would point out with Between Two Castles (and it may well be elevated even more if you don’t decide on tiles the way we did) is that the discussions between players can take up a reasonable chunk of the game. This isn’t too much of a problem in itself, as the game isn’t a long one, even when learning, but when I have played, there has always been one person not doing anything while their neighbour discusses their placement with their other neighbour. Again, it doesn’t tend to take very long, but if these potential moments in limbo would put you off, then it is something to consider.

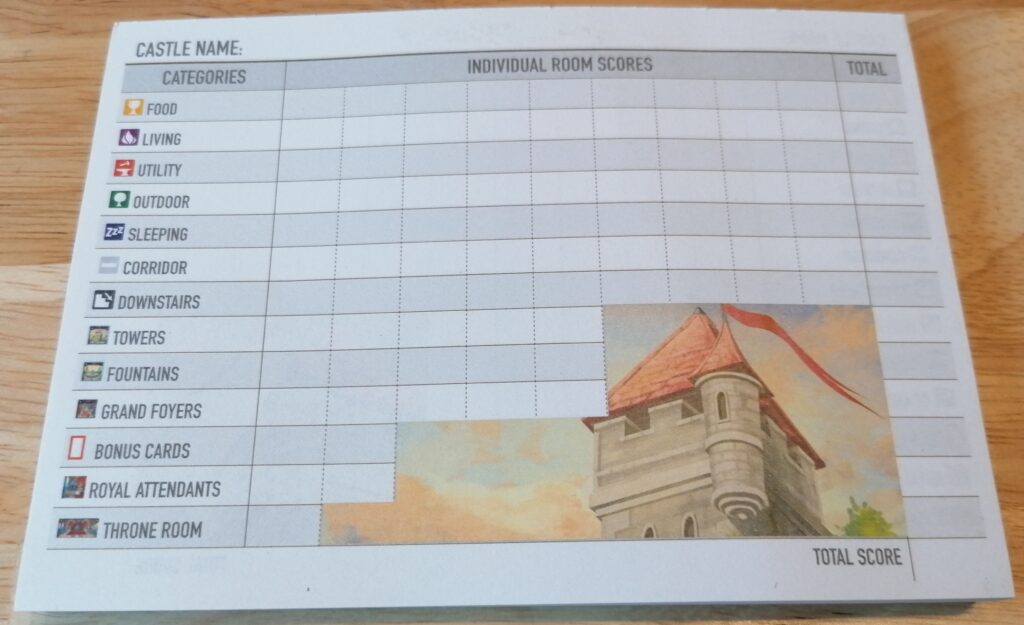

As with all the games published by Stonemaier Games that I have played, the production is brilliant, though Between Two Castles may take the crown. The art, for me is lovely, and very evocative of the theme. The wooden castle pieces, though unnecessary, as you only use them to place the tiles you are passing to your left or right underneath to indicate that you have chosen your two tiles, are nicely tactile. The scorepad is very good, as it gives you spaces to score every single room in your castle individually, saving you from using a calculator (or doing maths in your head) to add up all the types of rooms in one. But it is the trays that you receive with the game that make it.

Designed by a company called Game Trayz, not only do they act as a brilliant insert for the game, saving on plastic bags being used to store game components, they are incredibly functional for gameplay, setting up the game, and putting the game away. When you first sort out the game when you receive it, you’ll sort all the tiles into piles of nine and place one pile into each slot in the larger tray (with two pile of ten left over to place at the bottom of the tray to be use as spares) You’ll place all the bonus tiles and cards into the smaller tray, sorted into piles of the same types of bonuses. At the beginning of a round, all each player has to do is take one of the piles of nine, taking seconds where it could have taken minutes if the tiles were all in bags. Whenever you need to take a bonus, they’re all sorted into their own slot, meaning you’ll never have to go searching for the right one. And when you’re putting away the game, you’ll just need to sort the main tiles into piles of nine and place them back into their slots, put the bonuses back into their slots, and pack the game away. I haven’t come across any games which use these before, but if they all work like this, I am very much on board. You could say that they add to the price of the game, and that’s reasonable, but, as I’ve stated before, I’m willing to part with a little more money for quality components.

Between Two Castles of Mad King Ludwig is a fun, relatively simple, fairly quick game with a good amount of depth. I’m far from saying that this is a perfect game. I do find that the time waiting for your other players to discuss their placements while you do nothing takes me out of the game slightly. I think that, at least some of the time, your decision is fairly obvious as to which tile to use for one, or both, of your castles, which takes a little bit of the fun complexity out of the decision-making, despite what I said about it not being a ‘solvable’ puzzle. That said though, I do enjoy it, and I’d be happy to play it again.

| Prices delivered by BoardGamePrices | |

|---|---|

| Between Two Castles of Mad King Ludwig £35.66 with shipping, in stock! Buy now See all 28 offers! |